The Passport Professor – An Investment Migration Insider Exclusive Interview

Born in the former Soviet Union, he is keenly aware that the Rule of Law is what stands in the way of political autocracy, and he has strong opinions on what role the EU should play in shaping the international order. But enough about Vladimir Putin. Last week, Professor Dimitry Kochenov – together with co-publisher Dr. Christian Kälin of Henley & Partners – launched the 2nd edition of the Quality of Nationality Index in London.

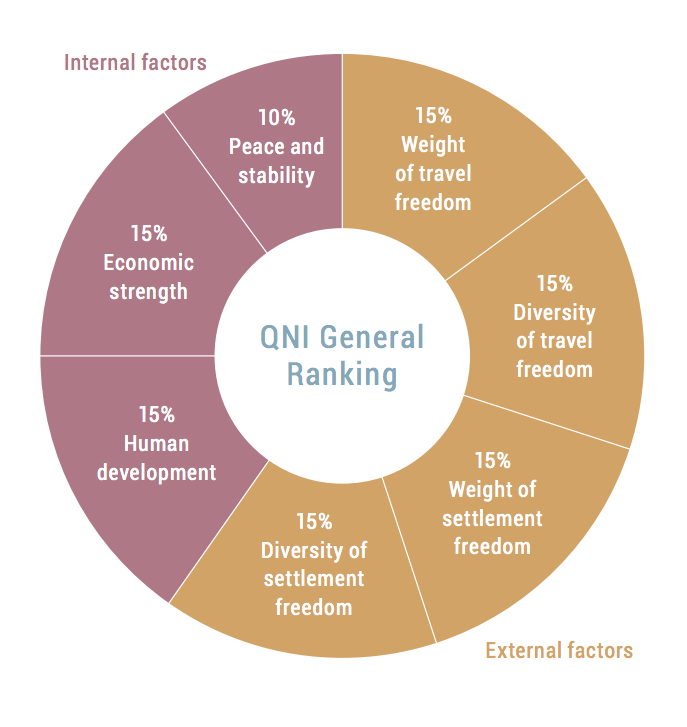

The Index aims to quantify the intrinsic value of a given nationality by way of objective measurements (see figure 1), and accounts for both “internal and external” factors. For instance, the number of countries someone with a certain nationality may visit without a visa counts toward that nationality’s external value, while the size of the domestic economy counts toward its internal worth. We’ll learn more about the Index’ methodology but, first, let’s introduce the subject of our interview.

Dr. Kochenov is among the foremost researchers on the topic of citizenship by investment. Born just 38 years ago in the city then known as Gorky (Nizhny Novgorod today) the prolific professor has already published ten books and more than a hundred articles.

Aside from serving as Chairman of the Board for the Investment Migration Council, he holds a chair for EU Constitutional and Citizenship Law at the University of Groningen, and has been a visiting scholar at a number of prestigious institutions of higher learning, most recently Princeton.

But don’t let the weighty credentials fool you; Kochenov is no garden-variety academic. His effervescent and unceremonious demeanor, ungovernable curly hair, chic spectacles and carefully selected bow-tie, combine to render an impression of a free spirit trapped in a (double-breasted) suit. A salonfähig bohemian, you might say.

The dissonance between Kochenov’s neatly pressed shirt and the week-old scruff on his chin is mirrored in his offbeat personality: half tactful gentleman, half irreverent ruffian. He can be as biting in his ridicule as he is effusive with his praise. He peppers his talks with clever quips delivered in flawless English (and with a thick Russian accent) that have the whole room rocking with laughter, charming audiences from Brussels to Dubai.

But he’s also not one to let debate-opponents raising poorly constructed arguments off easy. Most recently, it was Dan Hannan – perhaps the UK’s most public advocate for Brexit, save for Nigel Farage himself – who got to feel the sting of Kochenov’s trademark sharp wit: During a panel discussion in London on the occasion of the QNI’s 2nd edition launch, Kochenov remarked dryly that Hannan’s knowledge of the legal rights of EU citizens would not even be sufficient to pass exams at “the worst law schools on the outskirts of London”.

The refreshing contrast from the blandness of character so often observed among legal scholars has made Kochenov an audience favorite and a staple of migration-themed speaking engagements the world over.

Investment Migration Insider had the pleasure of talking with the professor about the QNI, as well as about where he believes the market for investment migration is heading over the next few years.

Investment Migration Insider: The QNI that you created with Dr. Christian Kälin is in many ways a meta-index in that it incorporates data from other indices. There is a great variety of factors that you could potentially include, for example, the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Ranking, or Mercer’s Livability Index. How did you decide where to draw the line?

DK: Since we wanted the QNI to be as objective as possible, we tried to avoid including perception-based measures and rather focus, to the greatest extent possible, on quantifiable factors that didn’t rely on opinions.

There are plenty of different indices ranking the quality in terms of lifestyle or ease of doing business and so on. But these indices incorporate perceptions rather than objective data, which is to say that they rely on the testimony of experts or friends or colleagues etc. This is the element we wanted to eliminate.

There were other elements I would have liked to include, such as military service requirements, but the data on this was incomplete, so I would have had to base this on perception, which would have been unfair. I drew the line where hard data ended and perceptions began.

And this is why the number of elements in the methodology isn’t that high, but they reflect very well what Dr. Kälin and I wanted to measure.

The Peace and Stability component of the methodology makes up 10% of the total, while the other components each make up 15%. Why is that?

DK: When peace and stability go down in a country, it frequently pulls several of the other components down with it, so that a reduction in peace and stability would be reflected by a reduction in the HDI and in economic activity and so on. So there’s a risk that if you give this component too much weight in the index, the changes in a country’s score would be disproportionate because a reduction in peace and stability would be counted 3-4 times.

We actually thought about not including this component at all but decided to leave it in because sometimes you see a deterioration in peace and stability a while before the effects of that show up in reduced economic activity, higher mortality rates, travel restrictions etc.

One important measure in the index is the degree and diversity of settlement freedoms. Many readers are well acquainted with the settlement freedom trends in Europe, but which trends are you seeing on this dimension in other regions?

DK: The interesting thing about this is that Europe is not an outlier. This was a discovery we made while preparing the index. There are more and more countries around the world opening up for visa-free travel and increased settlement freedoms. There are absolutely clear regional trends. The clearest trend is in Latin America, which is developing regional settlement agreements similar to those that have been in place in Europe for some time.

The same is true for the Gulf state nationalities, to some extent, but we are not sure what will happen there due to the recent tensions between Qatar and its neighbors. While they are a full Gulf Cooperation Council member, citizens of Qatar are, de facto, not welcome to settle anywhere else in the GCC right now, and were even asked to leave.

There’s a good chance the Gulf state nationalities will see significantly reduced quality by the time next year’s Index is out, as settlement freedoms within the region are changing.

There’s a similar concern in the former USSR. Ukraine is a good example. Before trouble started in the Ukraine and before the annexation of Crimea, the potential for a functioning free movement agreement allowing freedom of settlement among the majority of post-Soviet nations was much greater. Now, Ukraine has actually lost virtually all of its free settlement destinations.

A great degree of freedom of settlement is what separates the very top nationalities from the rest, and sudden geopolitical changes can easily cut that off entirely.

Also, the waning of colonial ties, which used to come with certain settlement freedoms, as was the case for Commonwealth country nationalities, is part of a separate, downward trend in settlement freedoms around the world. In the context of decolonization, numerous inhabitants of the Caribbean had settlement rights in the UK, for example, which they now don’t.

Russia’s former satellite state nationals have clearly seen a reduction in their settlement freedoms. In fact, I would not be surprised to see, ten years from now, a visa-wall separating Russia from its former satellite states.

So settlement freedoms related to regional integration and based on economic thinking are increasing, while those based on a shared colonial past are decreasing.

But on the whole, globally, there is a positive trend toward increased regional integration and reciprocal treatment of citizens. We definitely see this in the EU, in Latin America, the Gulf and with ECOWAS in Africa.

As an increasing number of countries enter the market for citizenship and residence by Investment, bringing the prices down, do you anticipate that someday, in the not-too-distant future, investment migration will go mainstream and become as common among upper-middle-income families as buying a second car or a holiday home?

DK: I think it’s already mainstream, it’s just that those of us holding the extremely high-quality nationalities don’t notice it because we’re not in the market for these products. But if you look at the, relatively speaking, medium-quality nationalities, such as China and Russia, you discover that plenty of people in the middle class, sometimes even lower middle class, hold, if not passports, at least residence permits abroad, because they can be acquired for relatively small sums of money.

We could also start seeing a sort of “Ryanair of residence permits” targeting the lower middle class. But those would, in any case, only be of interest to people of medium to high-quality nationalities, not low or high to very high-quality ones. People of extremely high-quality nationalities don’t really need any upgrades, and the vast majority of people with low-quality nationalities have economic conditions that would essentially necessitate bringing the investment requirements down to zero, which won’t happen.

So, in the end, if we’re talking about where the boundaries of this industry can be found, I think the market is in practice limited to holders of the middle-of-the-road nationalities. The investment migration industry is more or less invisible to the holders of the best and the worst nationalities. Of course, there are always exceptions, there are wealthy and successful people of all nationalities, but the question of scale is important.

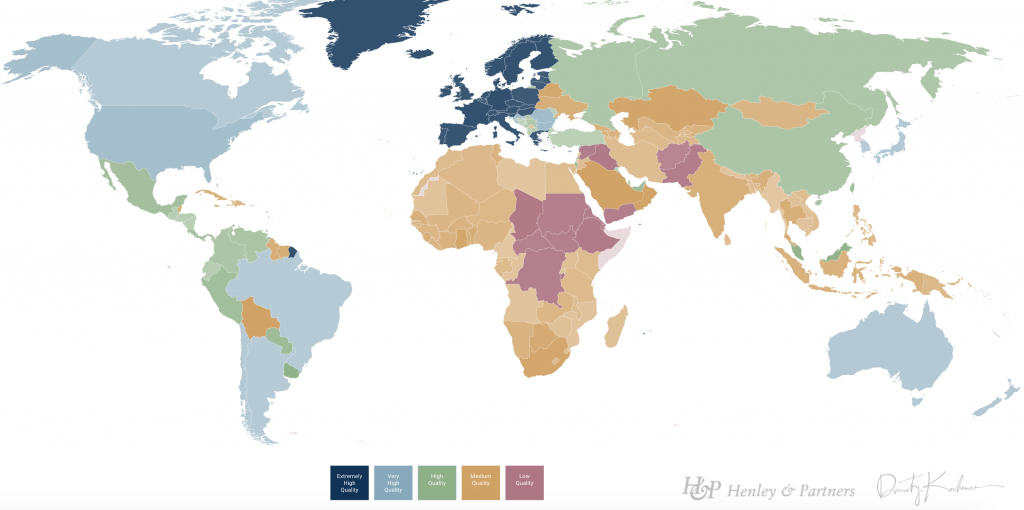

The index is very helpful in predicting industry trends because by looking at the colors assigned to each nationality, we can clearly map where the bulk of customers will come from in near and medium term. The customers will not come from the blue nationalities, and also not from the lilac and lower orange ones, but overwhelmingly from the upper orange and green.

To learn more and to see the detailed results of the Quality of Nationality Index, please visit the official website.

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.