The Most Transparent Citizenship by Investment Programs – Special Feature

Citizenship by investment programs across the globe differ markedly in their level of transparency. In this feature, we’ve enlisted the help of three experts to help us consider the degree to which transparency is necessary, when it is appropriate to restrain it, and which CIP countries do the best job of disclosing the relevant facts and figures about their programs.

Reconciling transparency and privacy

To CIPs, transparency is imperative chiefly for two reasons:

The first is that there’s no shortage of autocrats, eurocrats and demagogues (but, I repeat myself) just waiting for any excuse to shut down the whole citizenship by investment industry, just waiting for that one blunder that will give them the popular anger they need to outlaw the vulgar practice of selling something as sacred as nationality. We can’t afford to give them any more than we absolutely have to.

One way to do that, is to be as transparent as possible in terms of the criteria by which applicants are approved or rejected, in terms of the statistics about how many apply, where they come from, how much and in which ways they contribute, and about how the money raised through CIP is spent.

Ensuring transparency, however, is not merely a means of improving the industry’s image – although it certainly helps in that respect – but, just as crucially, it’s a preventive countermeasure to the latent cancers of graft, nepotism, and surreptitious arrangements that invariably metastasize in the absence of public exposure. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

But transparency, while a laudable ideal, must be balanced with the equally valid principle of privacy.

Many CIP applicants, such as those born into autocratic jurisdictions, have legitimate and morally justifiable reasons for wishing to limit the number of individuals and organizations aware of their second passport. It would be unconscionable, for example, to publish the addresses of CIP investors, particularly if they were extraordinarily wealthy and lived in a jurisdiction with high crime rates.

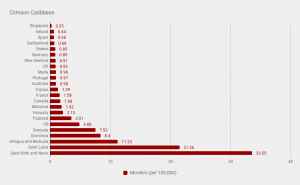

Read: The good, the bad and the homicidal: 23 investment migration destinations by security levels

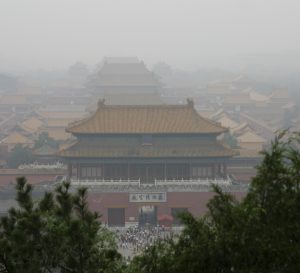

Similarly, publishing the names of applicants from certain countries could jeopardize their safety from unjust persecution, as well as complicate the CIP country’s diplomatic relations with the country of origin. Imagine a Caribbean ambassador, for instance, trying to explain to his counterpart from a hypothetical East Asian superpower (that expressly forbids its citizens from holding a second citizenship) why nationals of that hypothetical country have been granted a Caribbean passport, even as the granting authority knew full well that the country of origin did not permit it.

It’s safe to say it would be a fairly awkward conversation. The hypothetical East Asian superpower is, of course, fully aware that some of their citizens are getting second passports, but prefer to turn a blind eye to that (for now) so as not to upset any international apple carts in the midst of trade negotiations related to (purely hypothetical) belts and roads.

The two aims of transparency and privacy are in direct, zero-sum conflict and, since neither may be dispensed with in favor of the other, the industry continually grapples with the question of how to reach a compromise; where to draw the line between showing electorates, the media, and intragovernmental bodies that we have nothing to hide and, at the same time, demonstrating to applicants that their personal data will be respected.

The eight CIP countries each have their own way of striking that balance. Some err on the side of transparency, others on that of privacy, and none of them get it just right.

And: List of Cyprus CIP Citizens Leaked: Soros-backed Foundation Funded the Articles

Which CIP-countries are the most transparent?

We can determine a CIP’s level of transparency by looking at the degree to which it follows certain disclosure practices:

1.Does the program release statistical data on the numbers, names, and nationalities of applicants, the figures invested/contributed, and which investment options they chose?

2.Does the CIP release such statistical data in a uniform manner and with regular intervals?

3.Are the costs of operating a CIP publicly disclosed? I.e., how much is spent on marketing fees, commissions, CIU-employees and so on?

4.Does the CIP or the government disclose specifically how funds raised by the program are spent?

5.Is the data released by the processing body itself (i.e. the CIU or other government bodies), which would pose a conflict of interest, or by an independent third party or regulator?

6.Are the criteria by which applicants receive approvals or rejections objective, clear and publicly disclosed?

7.Are the methods by which due diligence is conducted sufficient, impartial, commensurate with international standards, and publicly known?

8.Are concessionaires, marketing agents, and other government advisors appointed according to objective, publicly known criteria and is the selection process conducted by way of public tenders?

9.Are the contents of the agreement between the government and the private companies whose services it enlists in the public domain?

With regards to the disclosure of information regarding applicant provenance, investment choices, and how governments spend CBI-funds, Dr. Hussain Farooq – President of HF Corporation, an investment migration firm – comments that “the data from all the countries may not be available to the general public, especially on how the funds are channeled for economic welfare. Some countries release reports on the funds gathered but don’t name the nationalities of the applicants, some name the nationalities and tell about the total funds raised, too, but how those funds are channeled is not known to the general public.”

Farooq’s statement resonates with James McKay – a researcher who, among other endeavors, has worked closely with CIP consultancy CS Global to develop a CBI-index in which Dominica came out on top – who points to a great degree of variance among CIP-destinations in terms of propensity to opening their books.

“Certain countries have tighter and more sophisticated checks both internally, when it comes to the sharing and checking of information with domestic police and law enforcement agencies, as well as externally, with sharing at the international-level Interpol, US, and EU databases etc,” writes McKay.

“So, in Europe for example, a country like Malta has strict requirements (at least on paper) in terms of the provision of police/business/funding records as well as enforcing [the exclusion of] a number of banned nationalities. Bulgaria’s programme, by comparison, is less scrutinous,” adds the researcher.

Professor Dimitry Kochenov of the University of Groningen – an introduction to whom would be gratuitous for regular readers of this publication – emphasizes, for the avoidance of doubt, that as inconsistent as transparency standards may be among the eight official CIP countries, they are all practically models of glasnost when compared to certain under-the-counter “programs”.

“The most non-transparent are of course the countries that do not have an investment migration programme on the books but are rumored to be offering investment migration opportunities,” comments Kochenov in an email.

Holding up the same example as McKay, the professor is categorical in his view of which of the official programs sets the standard in transparency:

“Malta is obviously the most transparent as it publishes who acquired citizenship by investment, allows for the audit of the programme by a regulator, and releases the data on the programme’s operation,” writes Kochenov, who also says that that, in addition to the necessary but not sufficient steps of publicly clarifying program requirements, reporting on figures raised, the number of approved and rejected applicants – which he asserts “there is no defense” for not doing – he maintains that all CIPs should instate an independent auditing body to “make sure the programs are not abused”.

The EU keeps CIPs on their toes

Kochenov indicates European Union membership has the effect of raising standards for program transparency due to the added pressures belonging to such an exclusive community entail.

“[…]Malta and Cyprus naturally stand aside compared with all the other programmes around the world due to the membership of the two countries in the European Union and a general climate of regulation throughout their administrations which has to be at a certain level to ensure successful functioning within the context of the EU legal system,” writes Kochenov.

“This is not because Cyprus is per se better than, say, Saint Lucia,” he continues, “but because Cyprus is — at least in theory, but also in practice — under constant binding supervision from the European Commission and the European Court of Justice, creating a radically different climate of accountability — EU Member States are answerable on a growing list of issues to the European Institutions in Brussels, Strasbourg, and Luxembourg.”

Read: EU Calls on Malta to Identify IIP-Citizens, Enforce Physical Residence Requirements

“So, if Malta or Cyprus take serious missteps in the design or management of their investment migration programmes, the pressure from Brussels will obviously be there and it is a great thing, strongly discouraging abuse: accountability is not only ensured within but also from outside the legal-political system of a concrete state.”

Though decidedly partial to the ideal of openness, Kochenov is also quick to point out that transparency is not unequivocally benign.

“There are pros and cons of such openness, of course; While it allows for the societal scrutiny of the programme, which is absolutely vital in any democracy, it could harm the prospects of the programme as such with the investors coming from jurisdictions intolerant of dual nationality,” he says, alluding to the abovementioned hypothetical East Asian superpower, as well as Ukraine, and also offers a novel solution to the conundrum investors from countries not permissive of dual nationality face when the government gazettes their names:

Kochenov suggests “allowing the applicants to ask the government to opt out from the publication of the name based on weighty reasons provided, such as holding citizenship of another country, which is intolerant to cumulation.”

Not having a public tender would be “outright illegal”

McKay points to the difficulty of imposing uniform standards on sovereign countries as a challenge in the pursuit of transparency.

“The overriding issue is that there exists no formal international body that regulates or oversees CIPs, making it challenging to get an accurate picture of relative performance. As that is not yet the case, my personal opinion is that CIPs, as de facto investment vehicles, ought to adopt standards as laid out by the investment industry pertaining to transparency, money laundering, and terrorism.

For example, this would include strict guidelines on PEPs and AML directives issued by the European Banking Authority and/or the jurisdictional equivalent. Due to jurisdictional differences, this is obviously an imperfect solution but would represent a small step to “anchor the goal posts” of transparency in CIPs.”

A common and not entirely unwarranted criticism of the industry is the dearth of insight it offers into the mechanisms by which concessionaires and marketing agents acquire their exclusive rights to counsel governments. All three experts agree that public tenders are a sine qua non.

“It’s clear that no programme is watertight in this regard,” says McKay. Kochenov admits he prefers not to point fingers but says an open tender process is critical and that “not having a tender in such cases would be outright illegal in any country with a developed legal system.”

Dr. Farooq, on his part, says information in this respect is scant and that whether the allocation of concessions in most cases is fair “would involve some perception on the commentator’s part. If someone asked the concessionaire or official marketing partners, or in some cases exclusive agents in some jurisdictions, their view may vary from other agents which may have lost the bid, or who aren’t involved in that program.”

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.